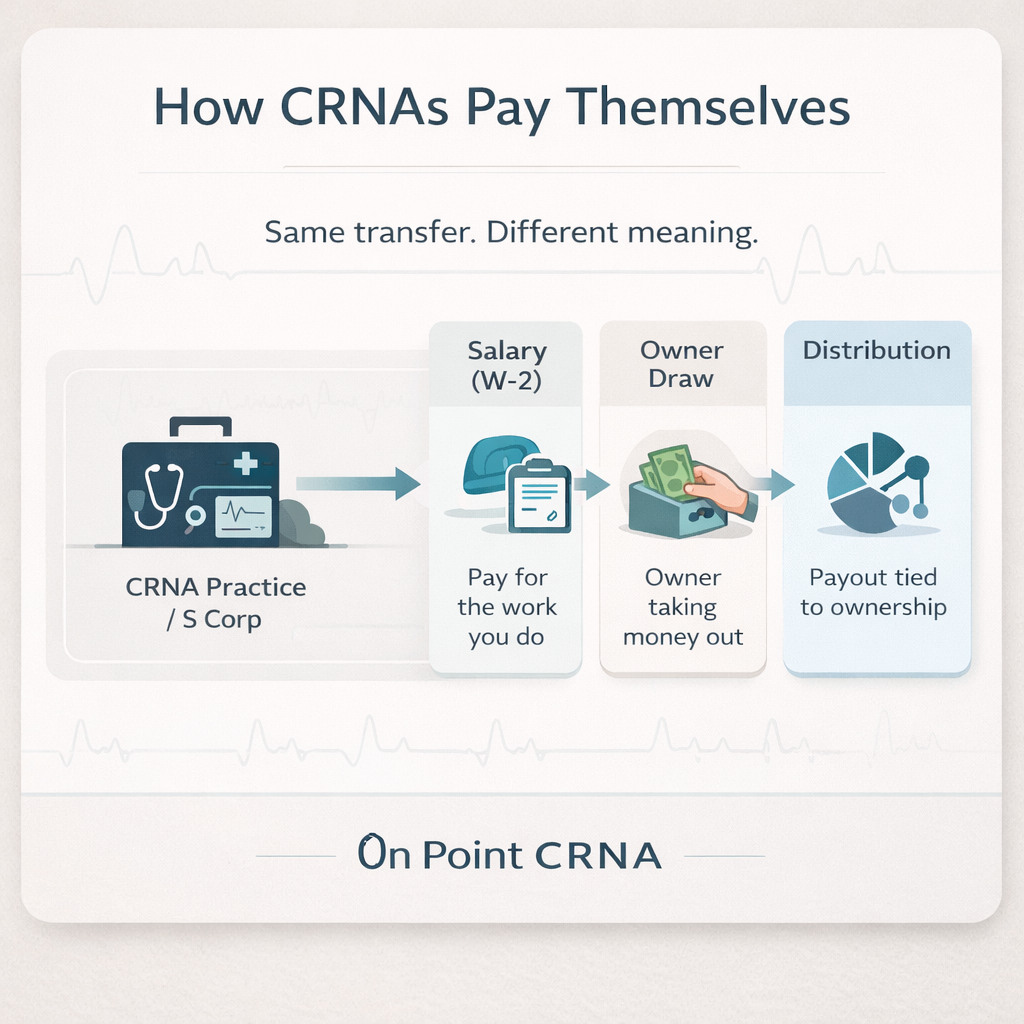

Picture this. You move $8,000 from your business checking to your personal checking. The bank calls it a transfer. You call it “owner pay.” Your life improves immediately.

Then your tax pro asks one question: “Was that payroll, an owner draw, or a distribution?”

Same money. Very different consequences.

If paying yourself from a business has ever felt like a tax-themed choose-your-own-adventure book, you are not alone. The tricky part is not the transfer. The tricky part is what the transfer means.

The 60-second cheat sheet

Before we go any further, here is the quick-and-clean vocabulary.

| Term | What it is (plain English) | Where it shows up | What it usually changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| W-2 wages (salary) | Pay for the work you do in the business | Payroll reports, W-2, and typically your Profit and Loss as an expense | Payroll taxes, retirement plan contribution room, and how “reasonable” your pay looks |

| Owner draw | Owner taking money out of the business (common for sole props and partnerships) | Balance sheet (equity), not as an expense | Cash flow and equity, but usually not the business profit number |

| Distribution | Owner payout tied to ownership (common for S corps and partnerships) | Equity section and owner reporting (varies by entity) | Basis tracking, how income is categorized, and sometimes payroll tax exposure (indirectly) |

One quick caveat: The “right” answer depends on your business structure and tax treatment. If you want the IRS version of that sentence, their “Paying yourself” page spells it out plainly.

Why this gets confusing fast

Most owners are doing two jobs at the same time:

- The worker: the person doing the actual work (seeing patients, selling, managing, producing).

- The owner: the person who takes the upside (profits) because they own the thing.

Wages are for the worker role. Draws and distributions are for the owner role.

Mix those up, and your bookkeeping can start telling a story that does not match reality. The IRS, lenders, and future-you all prefer boring, consistent, easy-to-defend stories.

Rule of thumb: If the money is for work, call it work pay. If the money is for ownership, call it ownership pay. Do not let “because it was Tuesday” be your accounting policy.

Your business type decides what “pay yourself” even means

This is where a lot of good people get tripped up. “I have an LLC” is a legal statement, not a tax statement.

- Sole proprietor (including a single-member LLC taxed as a sole prop): you generally do not pay yourself W-2 wages. You take draws. You pay tax based on profit.

- Partnership (including a multi-member LLC taxed as a partnership): owners typically take draws and may receive guaranteed payments for services. It is a different animal than W-2 payroll.

- S corporation: if you own it and work in it, wages usually need to be part of the plan. Then distributions can come after wages are handled.

- C corporation: wages and dividends are separate tools with separate tax effects.

Same business. Different rulebook. That is why one owner can do something that is perfectly normal, while another owner doing the same thing is basically waving a red flag.

Wages: paying for the work you do

Wages exist for one reason: to pay for labor.

Try this thought experiment: if you hired someone else to do your job, what would you pay them? That is the spirit of wages.

When wages matter most

- S corporations: If you own the S corp and you work in it, wages are not a “nice to have.” The phrase you will hear is “reasonable compensation.” (Yes, it is as fun at parties as it sounds.)

- Retirement plans: In many S corp setups, your retirement plan contributions are tied to W-2 wages, not distributions. If you want to max a Solo 401(k), wages matter.

If you want some official reading on the S corp wage topic, the IRS has a page specifically for it.

IRS: S corporation compensation and medical insurance issues

Common wage mistake

Calling everything a distribution because it feels cleaner. It might feel cleaner today. It can feel a lot less clean later if the wage number does not pass a basic smell test.

Owner draws: taking money out (without calling it payroll)

Owner draws are simple. You take money out because you are the owner.

The part that surprises people is this: an owner draw is usually not a business expense. It is not “payroll.” It is a reduction of owner equity.

Translation: you can take draws all year long and still owe tax on the business profit you earned, even if the cash is gone. Not my monkeys, not my circus, but it is a very common surprise.

Where draws show up most

- Sole proprietors

- Single-member LLCs taxed as sole proprietors

- Partnerships and multi-member LLCs taxed as partnerships (often alongside other owner pay mechanics)

If you are in one of these structures, the “how do I pay myself?” question is usually less about the transfer and more about tax planning, estimated payments, and clean bookkeeping.

Distributions: paying yourself as an owner

Distributions are owner payouts tied to ownership. They are not payment for labor.

In plain terms: wages are the paycheck for doing the job. Distributions are the payout because you own the company that made money.

Why distributions are popular

Because, in some structures, distributions can reduce payroll tax exposure compared to treating everything as wages.

That is also why distributions get a little extra attention. The moment distributions show up, the “reasonable wage” conversation usually is not far behind.

Why the label matters beyond taxes

Taxes are the headline, but they are not the only reason to get this right.

- Retirement contributions: W-2 wages often drive how much you can contribute in certain plans.

- Loans and mortgages: underwriters love clean, consistent income documentation.

- Bookkeeping sanity: clean categories now beats a clean-up project later.

- Defensibility: if you ever have to explain your setup, you want a story that makes sense.

A quick case study: two owners, same transfer, different meaning

Let’s say two business owners each move $8,000 per month to their personal account. Same amount. Same bank transfer. Two totally different stories.

Case 1: Chris (sole proprietor)

- Chris runs a solo practice as a sole proprietor.

- Chris takes $8,000 per month as an owner draw.

- At tax time, Chris owes taxes based on the business profit, not based on the draws.

For Chris, the planning problem is usually: “Did I set aside enough for taxes and retirement while I was paying bills?” The draw itself is just cash movement.

Case 2: Taylor (S corp owner who works in the business)

- Taylor runs the same kind of operation, but elected S corp taxation.

- Taylor also takes $8,000 per month, but calls all of it distributions and pays no wages.

For Taylor, the planning problem is different: “If I am doing real work here, does my pay structure look reasonable?” The same transfer now bumps into payroll rules and reasonable compensation expectations.

Neither owner is “bad.” They are just playing under different rulebooks.

Why this usually shows up later

Wage and distribution issues rarely cause immediate problems. Money still moves. Bills still get paid. The business keeps running.

The friction tends to show up when:

- income grows

- your role changes

- the business becomes more profitable

- you apply for lending or a mortgage

- multiple years get viewed together

At that point, the question shifts from “Did this work?” to “Does this still make sense?”

The goal is not precision. It is reasonableness.

This is the part people overcomplicate.

Owner pay is rarely about finding the perfect number. It is about choosing numbers that reflect reality well enough that you can defend them without breaking into a sweat.

- Reasonableness creates consistency.

- Consistency creates clarity.

- Clarity makes everything else easier.

If your pay structure tells an honest story about how the business runs, it stops feeling heavy. It fades into the background. When something fades into the background in planning, it is usually doing its job.

Common mistakes that create avoidable messes

- Mixing personal and business spending and hoping the bookkeeping “figures it out.” It will, but not in the way you want.

- Changing the label every month depending on mood, cash flow, or vibes.

- Paying yourself randomly and doing a clean-up project at tax time every year.

- Running an S corp and treating distributions like a substitute for wages.

- Forgetting the boring stuff like documentation, payroll filings, and clean categorization.

If you want a phrase to remember: the IRS does not care what your banking app memo line says.

How to set this up without overthinking it

- Know your entity and tax treatment. Confirm how you are taxed, not just how you are legally formed.

- Separate work pay from ownership pay. Decide what portion is wages (work) versus draw or distribution (ownership).

- Pick a cadence. Monthly payroll, quarterly distributions, periodic draws. The goal is consistency, not perfection.

- Document the decision. Notes, payroll reports, minutes, a simple policy. Something that shows you did not spin a wheel.

- Review annually. When income grows or your role changes, revisit the numbers.

Quick checklist

- My business bank and personal bank are not playing tag anymore.

- I can explain, in one sentence, why each transfer is a wage, draw, or distribution.

- If I have an S corp and I work in it, I have a wage number I can defend as reasonable.

- I am setting aside money for taxes, not hoping future-me enjoys surprise bills.

- My bookkeeping tells a consistent story from year to year.

Bottom line

Paying yourself is not about making the money move. It is about labeling the money honestly.

Once you separate “pay for work” from “pay for ownership,” the rest gets dramatically less intimidating. You stop guessing. You stop cleaning up messes at tax time. And you can focus on the part of business ownership that is actually fun.

Disclosure: This article is for educational purposes only and is not tax or legal advice. Talk with your CPA or attorney about your specific situation.